Brookdale Hosts Land Acknowledgement Ceremony on Indigenous Peoples’ Day

October 11, 2022

“After centuries of displacement and dispossession, acknowledging original native land is complex,” said Claire Garland, a member of the Sand Hill Lenape of Monmouth County and New Jersey.

Garland spoke to Brookdale students, faculty, and guests Monday (Oct. 10) at a Land Acknowledgement Ceremony for Indigenous Peoples’ Day.

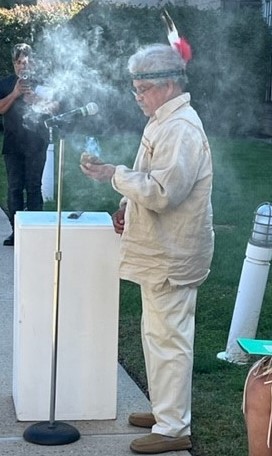

The ceremony began with Fortune Thomas, Garland’s brother, burning sage in a special vessel. This was done as a spiritual cleansing or blessing, Thomas said. He then offered a prayer of thanks for the attendees and for the opportunity to acknowledge that this was once his ancestors’ lands.

Garland, an advocate for Indigenous Peoples’ history and rights, is a member of the New Jersey Commission on American Indian Affairs. She spoke of the significance of this day.

“This acknowledgement is intended to recognize those people who have lived where we now work, over a long span of human history,” she said. “History didn’t begin with Columbus in 1492.”

Estimates of the native population at the time of Columbus’ arrival is somewhere around 100 million inhabitants. What happened after his arrival has been described as possibly the greatest demographic disaster in the history of the world. By 1650, the population declined to less than six million.

Garland provided important historical information about local Native American history, including the Indigenous Lenape inhabitants who were the original inhabitants of much of New Jersey.

Quakers facing persecution in New Amsterdam (New York) sailed across the bay and started buying up the land that is now Monmouth County.

The area now called Eatontown, hundreds of acres, was sold in 1670. Payment was a barrel of cider.

The land where Brookdale now stands was bought from Indigenous people by William Leeds, a missionary from England, on July 16, 1684.

Until Europeans appeared, Indigenous people believed in communal rights to property with everyone sharing in the land’s riches. When they “signed” deeds (mostly by making a mark like an X), they thought of them like leases. The European concept of hard rights to property essentially let the Europeans steal land.

“Native heritage is all around us beginning with the names that we use every day,” explained Garland. “These names were on the original deeds, and thus were kept.”

Navesink, Cheesequake, Manasquan, Matawan, Rumson, Manalapan, Mahwah, Secaucus, Weehawken, Hoboken, Manhattan, Hackensack, Paramus, Ramapo, Rahway, Raritan, Rockaway, Teaneck, Watchung, Wickatunk, just to name a few.

Also, Wanamassa was a chief; Pontiac was a chief, and Cadillac was a chief.

Wearing a handmade traditional fringed leather dress, Garland said her ancestry is a mix of native Lenape, Cherokee and colonial Dutch. Official tax records indicate her family was living in Tinton Falls in 1780. “My family has been here before there was a Monmouth County or a New Jersey,” she said.

After the ceremony, a collection of artifacts, including a ceremonial peace pipe made by Garland’s family, were displayed in the Center for Visual Arts Gallery. Students and faculty were encouraged to handle the items and visualize their use for a better grasp of their significance.

A group of architecture majors attended the ceremony and gallery as well as being a part of this living history experience.

Guadalupe Bautista Bueno said that although she had read about the Lenape history, being able to hear from someone who had a personal connection to that experience made it more meaningful.

Keishon Taylor shared Bueno’s enthusiasm and said he was “curious and wanted to learn more” about how the land and race acknowledgement would be handled.

Gabriela Pancheco felt it was a very different experience, reading about it on the internet and hearing Garland speak. “I wanted that first-hand experience.”

Alistair Kam shared that he is not from this area and just wanted to know the history of his school.