Remembering Sandy’s Devastation And Monmouth County’s Resilience

October 28, 2022

“Once the flood waters started coming in and trees started falling all around us, there was nowhere to go,” said Brookdale Associate Vice President William Burns remembering Superstorm Sandy, which struck the area 10 years ago.

“My wife and I decided to ride out the storm in our Manasquan home – something I would never do again,” said Burns. “I thought it wasn’t going to be as bad as it was. Looking back, it was a foolish decision.”

“We watched the flood waters rise and crash through my basement windows and destroy the furnace and everything else in that area. But we were lucky, compared to my neighbors, whose homes were flooded or heavily damaged. The water stopped inches from my front door, and so the damage to my home was actually minimal.”

Burns isn’t the only one recalling the devastation that rocked Monmouth County and beyond on Oct. 29, 2012 and the long-lingering effects.

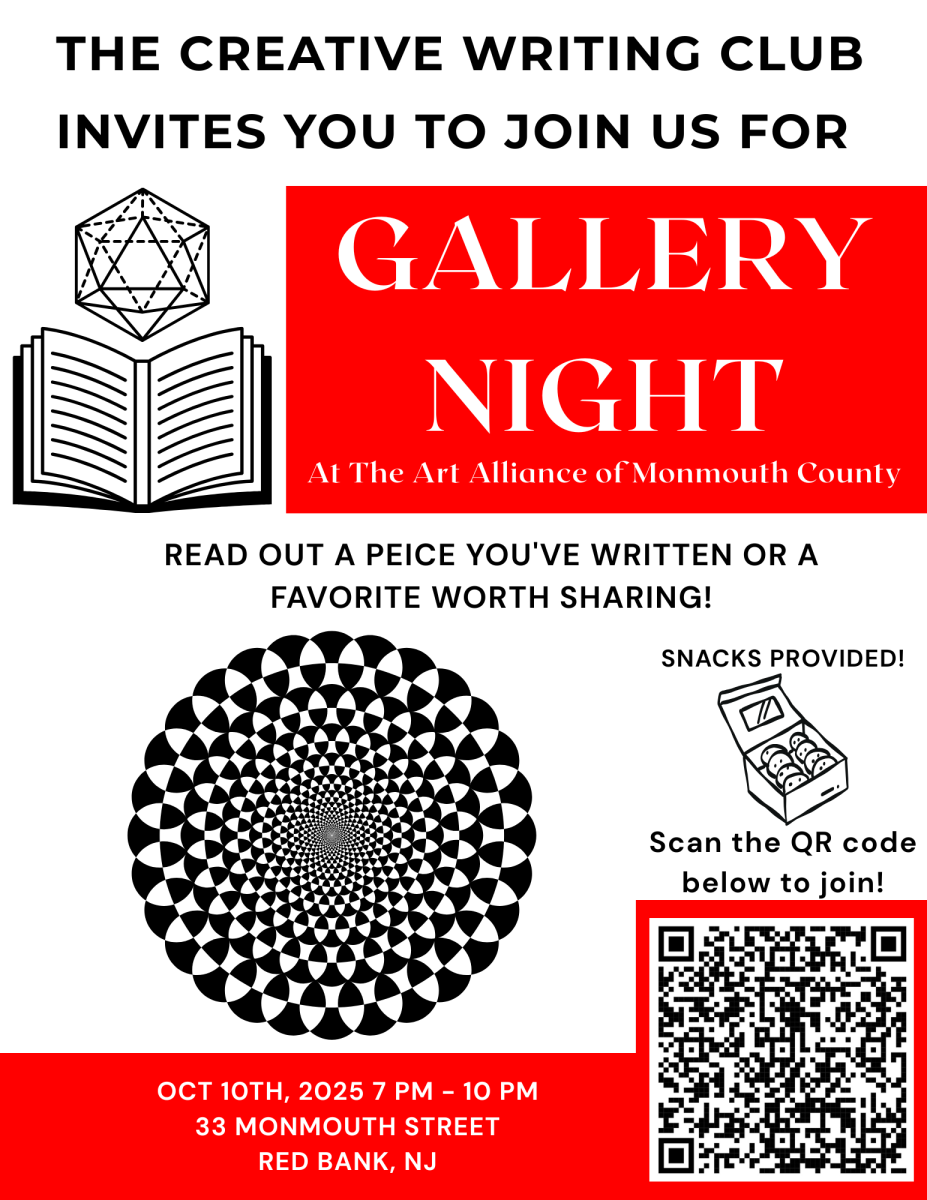

About a year after Hurricane Sandy, Burns, who was the Dean of Arts and Communication at the time, pulled together a Sandy Retrospective exhibit at Brookdale’s gallery in the CVA building. Photos, stories and memorabilia were shared and told the story of a community devastated but already rebuilding from its loss.

As the tenth anniversary approaches, many are reflecting on what was lost and how the area has changed, while others focus on how far the county has come and the resilience residents have shown.

For the central and south Jersey areas in the days just after Sandy, the lines for gas were miles long, and those stations that were still functioning, quickly ran out of gas. Four-hour waits were not uncommon.

Many roads were blocked by fallen trees and downed power lines. For those roads still accessible, there were no traffic lights operating. Most highways prohibited access onto crossroads, instead funneling left or right turns onto designated turning areas, often miles apart. Driving at night was dangerous, and unless for work or an emergency, few ventured out.

“Monmouth County was so devastated by Sandy – so many of my students and colleagues suffered incredible losses,” said Roseanne Alvarez, a professor of English and WILL program coordinator.

“I was living in the West End neighborhood of Long Branch at the time. I remember walking down Brighton Avenue to see what had happened closer to the water. The shops were boarded up, and the boardwalk was destroyed and inaccessible. There was this deviant graffiti message, ‘Sandy don’t slice us’ on a boarded-up pizza restaurant. It was on point. Despite it all, folks came together to help one another survive and rebuild,” she said.

In stricken areas, schools became makeshift shelters. The Keyport Central School housed close to 200 Monmouth County residents left homeless by the storm. The school became a foodbank of sorts as hundreds of families from nearby towns lined up for miles to donate food and needed items. This donation-train lasted for weeks.

“For my family, it was the anticipatory fear that I remember,” said Brookdale student Antonio MacAluso, 19, a journalism major from Monmouth Beach. “I was only 8 years old, but my brother, sister and parents were forced to evacuate as floodwaters rose, flooded our garage and threatened to overtake our house.”

“We were lucky,” said MacAluso. “When we returned, we only had minor flooding.” He was shocked to find nearby homes destroyed. Schools were closed, and the National Guard was stationed near his home, both to help maintain order and to distribute water to Sandy’s victims.

As devastating as the storm was, no one was prepared for the aftermath.

“I had a student who used to drive to his former home in Union Beach every day after the house was torn down to play basketball on his former driveway court. In the chaos of post-Sandy life, it made him feel normal,” said Debbie Mura, a communications professor.

Mura, who suffered devastating losses to her home in Toms River, shared a story about another student: “She had just gotten engaged. They bought a house in Freehold where a couple had lived for 35 years and planted a tree every year on their anniversary. She and her fiancé thought that this was a good omen, but the storm uprooted the trees and caved in their roof.”

Malls, stores, businesses and homes were all without power. As the days without electricity turned into weeks and the weather chilled, those with generators used them judiciously. Gas was hard to obtain, and most generators offered only a few hours of intermittent power a day.

“For those of us in the eye of the storm – Ortley Beach and Seaside – the mandatory evacuation of our town became a mandatory forbidden zone,” said Colleen Paolo, 70, now of Boca Raton. “We were not allowed to return or check on our houses for almost a week.”

“When the police escorted us back, we were given less than an hour to view the damage, grab anything we could, and leave the area again. Armed guards patrolled the streets. My house had been under water, everything I owned was destroyed, and I, my husband, my son and my dogs were homeless and lived in 13 homes for the next three years.”

“You never fully recover,” Burns said. This echoed with all of Sandy’s victims.

“You don’t realize the long-term effects and how events trigger a response, even now, 10 years later,” said Paolo. “Watching Ian hit Fort Meyers was crushing, and I immediately donated to Samaritan’s Purse, the group that helped my family rebuild.”

Official White House Photo by Sonya N. Hebert