Of all the classes I had in grade school, I always liked history. For others, remembering names of generals or what revolution happened where was what made their history classes nightmares. But for me, I loved memorizing all the dates and complexities of conflicts and would read history books and novels outside of school.

Growing up, this love of history followed me. One of my first classes at Brookdale was a World History class with Professor George Reklaitis. Recently, I also decided that I wanted to expand my historical knowledge beyond what I knew about the wars and events in Europe that are taught through school.

I specifically wanted to know more about the colonization of Africa, a topic that is still incredibly relevant today. The colonization of Africa wasn’t something that happened overnight but was an era of European philosophy that slowly demanded more and more oppression and occupation upon an entire continent. It’s a deeply unsettling subject of history to study, which was all the more reason I decided I wanted to understand it better.

For those reasons, I chose to read “In The Forest Of No Joy” by J.P. Daughton. It’s a relatively short book on the Congo-Ocean, a railroad project orchestrated by the French colonial government in the Interwar period. Author J.P. Daughton is a seasoned historian who has taught at some of the nation’s top universities and written for “Time” and the “Atlantic” magazines.

“In The Forest Of No Joy” is a brutal story of how the French government oppressed thousands of their colonial subjects for the railroad project in the Middle Congo. France had gained control of the region in the late 1800s and after the Berlin Conference. This was a series of meetings where European empires agreed among each other where the lines would be drawn for their colonies in Africa.

The French always had little control over their territories of Middle Congo, Gabon, Ubangi-Shari and Chad. This meant that the corporations and administrators that were in the region had few authority figures there to control them. This lack of control led to regular abuse of African laborers by companies and lonely teams of administrators. The worst stories are of French officials killing innocent civilians for no reason other than they had the power to do so.

What’s most disturbing is that when such events happened, abusive administrators were barely punished. Courts immediately dismissed the testimonies of Blacks recalling stories of violence because of their race and would even find reasons to defend acts by the guilty party to reduce their sentence.

Stereotypes of the native populations dominated how the French government operated in Africa. There wasn’t a single conversation of the colonies without the French citing the natives as their own worst obstacle. Overtime, the French government saw it as their responsibility to help “fix” the native’s way of life, without involving the people affected at all.

“To many Frenchmen, the empire’s inhabitants—especially in Africa—were trapped in stagnant societies plagued by superstition, cannibalism and tyrannical political practices,” wrote author J.P. Daughton. “Colonial reformers thought in terms of what their subjects lacked: knowledge, political stability, and—crucially—technology.”

After the first world war, the French government was in financial disaster. So, politicians turned to the overseas colonies, looking to extract natural resources. For their Congo possessions, that meant building a railroad roughly 320 miles long from the administrative center of Brazzaville to the port of Point-Noire.

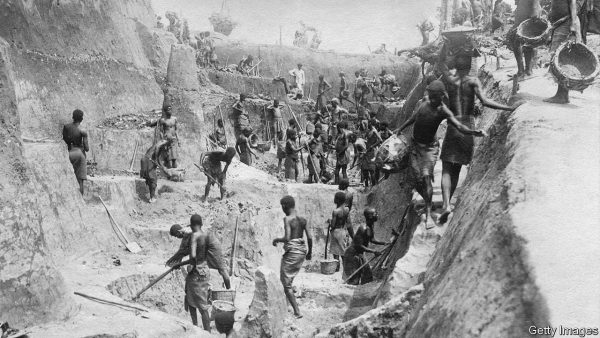

Construction took a brutal 13 years, from 1921 to 1934. It almost entirely relied on “volunteers” from villages across the region, including men and women hundreds of miles away. For many of those “volunteers,” they were put in chains and shackles, marched on foot and put into overcrowded boats in a river that sent them to the worksite.

For the first few years of construction, no modern machinery was given to workers. They were given nutritionally lacking rations that a doctor described as “‘manifestly insufficient.’” Workers walked several miles from temporary camps to the worksite every day. Mass graves were never far from the worksite either, as anywhere from 15,000 to 60,000 died building the Congo-Ocean railroad.

“In The Forest Of No Joy” is not a pleasant read. It’s a story of how a racist and ideologically blind colonial power destroyed an unknowable number of lives and communities. All in the pursuit of a single measly railroad that went on to deliver disappointing amounts of raw materials to Point-Noire.

J.P. Daughton frames the story of the Congo-Ocean in as accurately possible way. Because the lives of the workers were rarely recorded by French officials at the time, he had to rely on the independent and third-party sources of which there is a decent amount, since French administrators were not shy in presenting the construction of the railroad as a massive effort that resulted in many deaths.

One of the saddest parts of understanding the construction is that it wasn’t a single leader or army responsible for what took place. It was bureaucracy that saw each African laborer as a number on some paperwork. The problems on the worksite that were reported back to administrators were “solved” through new regulations. Regulations that weren’t applicable to the on-the-ground situation. Regulations that didn’t sufficiently meet the needs of laborers. Regulations ignored by abusive administrators on the worksite.

So the bodies piled up. Disease, malnutrition, worksite incidents and the anger of the administrators overseeing the laborers killed thousands. To this day, the loss of young men and women from their communities for the construction of the Congo-Ocean still effects the independent Republic of the Congo.

There is so much more to the crimes against humanity that were carried out on the worksite. But J.P. Daughton does an excellent job of explaining how the mindsets of Europeans led them to commit such horrible acts and still believe they were in the right. Overall, “In The Forest Of No Joy” is a good start to understanding the darker major events of history and the colonization of Africa.