Anti-Apartheid Activist Tells BCC Students, ‘You Have The Power To Change Things’

February 27, 2023

“What was your motivation?” a student asked Caroline Hunter, the woman responsible for starting a movement that ended America’s role in South Africa’s apartheid. Hunter responded, “That someone was suffering because of something I did or did not do.”

In the sobering midst of the realities of racism and mistreatment, a message of self-empowerment echoed through all the presenters at Brookdale’s Feb. 23 Black History Month event, “Truth To Power: A Conversation with Caroline Hunter.”

“We are in the room with greatness,” said Professor Gilda Rogers, who teaches history at Brookdale and is the Executive Director of the T. Thomas Fortune Cultural Center in Red Bank. “Caroline used her voice to literally change the world. She was one person. Others heard her and then more came. But it started with just one person.”

Brookdale student Kenneth Grant, a 19-year-old media studies major from Matawan, gave a dramatic reading of “blue/black blindness,” a poem by reg e. gaines, a Jersey-born, two-time Tony and Grammy award nominee.

Brookdale student Kenneth Grant, a 19-year-old media studies major from Matawan, gave a dramatic reading of “blue/black blindness,” a poem by reg e. gaines, a Jersey-born, two-time Tony and Grammy award nominee.

Ewurafua (Effi) Acquaah, who will graduate Brookdale in May with an associate’s degree in humanities, performed an original monologue woven into an introduction of Hunter, expanding on courage and commitment to correct injustices locally and around the world.

“How will we change the world?” Acquaah asked. “Through our voices, through our writing, through the artistic images we create. And by teaching, by gathering like-minded people to organizations that harness the power of many.”

“How will we change the world?” Acquaah asked. “Through our voices, through our writing, through the artistic images we create. And by teaching, by gathering like-minded people to organizations that harness the power of many.”

Rogers then introduced Hunter, asking questions as the two sat side by side, sharing the audience’s awe of Hunter’s accomplishments.

“I did not know the details of Caroline’s story,” began Rogers. “But I learned that someone here in America took a stand that started the domino effect of what happened in South Africa, and developed into the rise of a President Nelson Mandela. Courage is not lacking fear but rather a judgment that something else is more important than one’s fear,” she said, quoting from a poem by Ambrose Redmoon.

“I stand on the shoulders of greatness – I am not here by myself,” Hunter said.

Hunter was born in New Orleans, Louisiana in 1946, the fourth of six children. While acknowledging the important role her mother played in her life, Hunter attributes her successful education to Sister Katherine Drexel. A Catholic nun, Drexel was a wealthy heiress who devoted her life and fortune to educating underprivileged Native-American and African-American children. Hunter was one of the beneficiaries of Sister Drexel’s generosity.

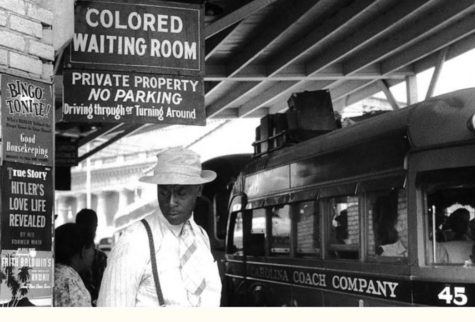

Being forced to ride in the back of the bus as a child on her way to school in segregated New Orleans was Hunter’s first taste of racism.

“I had to sit behind the sign,” she explained. “That means that if a white person got on the bus, I had to get up and move to the back of the bus behind ‘the sign’ (Colored people only). This was America’s apartheid.”

Hunter grew up in the segregated South, forced to drink out of “colored” water fountains, ride in the back of the bus and unable to eat at lunch counters or use department store dressing rooms, yet she learned how to use her voice.

Hunter grew up in the segregated South, forced to drink out of “colored” water fountains, ride in the back of the bus and unable to eat at lunch counters or use department store dressing rooms, yet she learned how to use her voice.

A good student, Hunter went on to earn a degree in chemistry and was hired as a research chemist for Polaroid in 1970.

While working for Polaroid, Hunter and her co-worker and future husband, Ken Williams, discovered that the company had an apartheid-promoting contract with the South African government to produce the photos used in the oppressive racist passbook credentials. These passbooks were designed to control where the indigenous African people could reside or where they could find employment.

“The passbook, a 60-page document the size of your passport had your photograph in it and your life record. You could be stopped by any white person at any time and if you didn’t have your passbook, you would be fined and/or sent to jail or experience whippings or beatings,” Hunter said.

When confronted, Polaroid denied the allegations. Caroline had proof that the company lied and held a rally with a South African divinity student who verified that yes, his passbook photo was taken by a Polaroid camera, as was everyone else’s.

Polaroid’s financial incentive was immediately clear – there are 22 million people required to have these photos – and Hunter along with her husband, founded the Polaroid Revolutionary Workers Movement, which gathered supporters and called for boycotts of Polaroid’s products.

Her journey that began with confronting Polaroid officials and organizing boycotts eventually led to speaking at the United Nations Special Committee on Apartheid.

“George Houser led the American Committee on Africa and was the person who helped us get an audience at the United Nations, which was my greatest honor,” Hunter said.

Then she testified before Congress and the U.S. Foreign Relations Committee. Her work expanded and spread to churches, businesses and schools and lasted for over seven years.

“We started it all,” Hunter said. “We used whatever method we could – the media, leafletting, hanging and distributing flyers, to get out our messages – we said DIVEST!”

Her bravery and commitment to fight injustice led to the divestiture out of South Africa by Polaroid, but not without a struggle, which included losing her job and racist threats against her life.

While acknowledging the difficulties and challenges of the path she chose, Hunter is justifiably proud of her accomplishments. She urged students to find their passion and then pursue it.

“You have the power to change things!” she said but warned that “there is no instant gratification – one must spend the time and put in the work to accomplish your goals.”

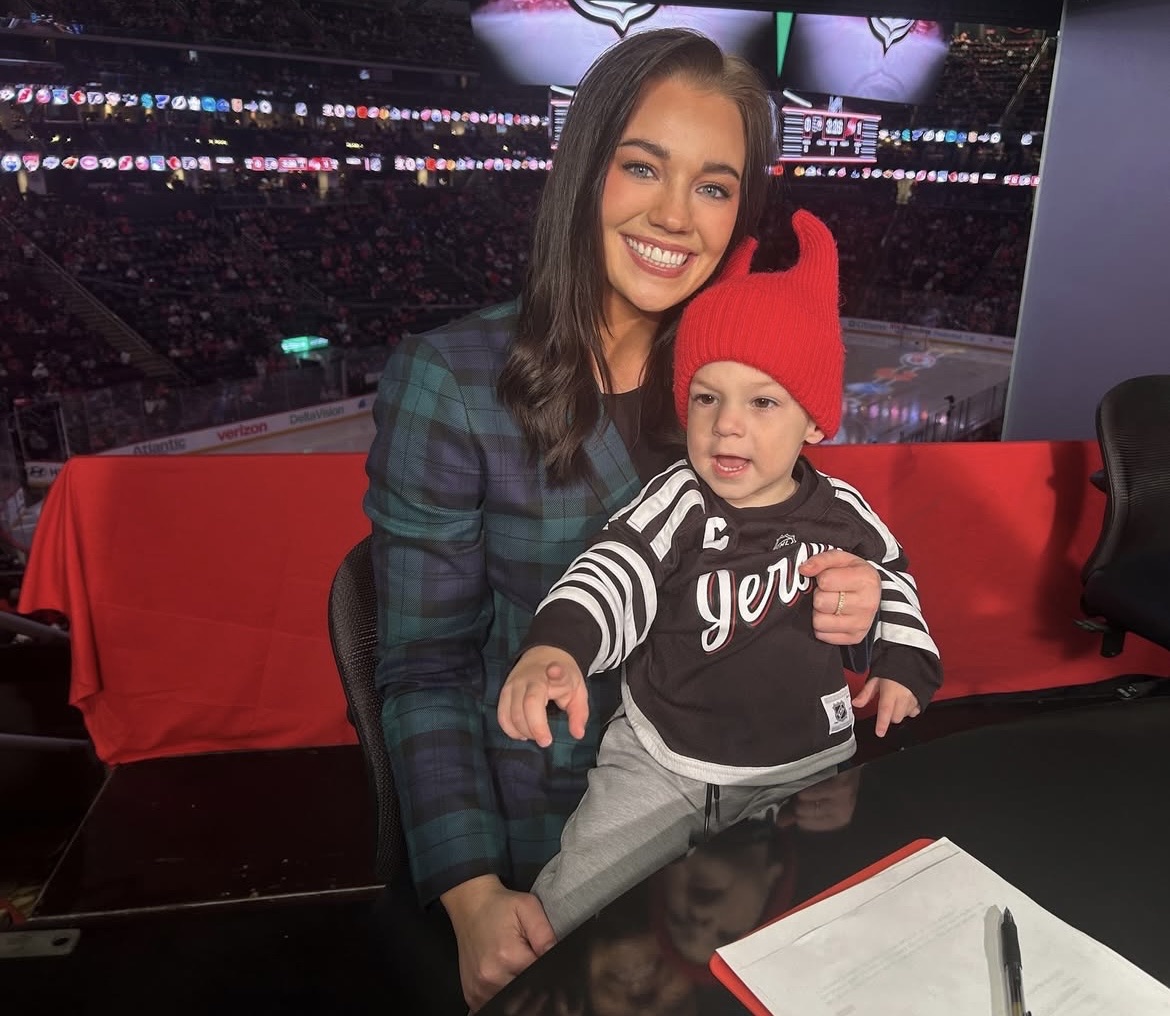

Event Photos By Isabel Shaw